The concert starts…a few bars from your favourite song…and moments later you’re swept up in the music, happily tapping your foot, clapping your hands and swaying along. (Unless it’s a classical music concert in which case you’re probably doing this much more quietly…) You look around. All around, people are doing the same. Many are singing, concert lights flashing to the rhythm, while other fans are clapping in time. Some wave their arms over their head, and others dance in place. The performers and audience seem to be moving as one, synchronised to one another as the light show is to the beat.

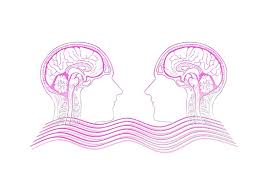

A new paper in the journal NeuroImage has shown that this synchrony can be seen in the brain activities of the audience and performer. And the greater the degree of synchrony, the study found, the more the audience enjoys the performance. This result offers insight into the nature of musical exchanges and demonstrates that the musical experience runs deep: we dance and feel the same emotions together, and our neurons fire together as well.

In the study, a violinist performed brief excerpts from a dozen different compositions, which were videotaped and later played back to a listener. Researchers tracked changes in local brain activity by measuring levels of oxygenated blood. (More oxygen suggests greater activity, because the body works to keep active neurons supplied with it.) Musical performances caused increases in oxygenated blood flow to areas of the brain related to understanding patterns, interpersonal intentions and expression.

In the study, a violinist performed brief excerpts from a dozen different compositions, which were videotaped and later played back to a listener. Researchers tracked changes in local brain activity by measuring levels of oxygenated blood. (More oxygen suggests greater activity, because the body works to keep active neurons supplied with it.) Musical performances caused increases in oxygenated blood flow to areas of the brain related to understanding patterns, interpersonal intentions and expression.

Data for the musician, collected during a performance, was compared to those for the listener during playback. In all, there were 12 selections of familiar musical works, including “Edelweiss,” Franz Schubert’s “Ave Maria,” “Auld Lang Syne” and Ludwig van Beethoven’s “Ode to Joy.” The brain activities of 16 listeners were compared to that of a single violinist.

All the musical pieces resulted in synchronisation of brain activity between the musician and listener, but this was especially true of the more popular performances. Interbrain coherence – the connection between the brains – was insignificant during the early part of each piece and greatest toward its end. The authors explained that the listener required time to initially understand the musical pattern and was later able to enjoy the performance because it matched that person’s expectations.

All the musical pieces resulted in synchronisation of brain activity between the musician and listener, but this was especially true of the more popular performances. Interbrain coherence – the connection between the brains – was insignificant during the early part of each piece and greatest toward its end. The authors explained that the listener required time to initially understand the musical pattern and was later able to enjoy the performance because it matched that person’s expectations.

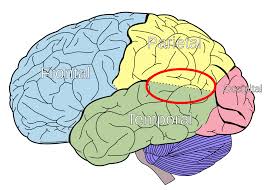

Synchronous brain activity was localised in the left hemisphere of the brain, to an area known as the temporal-parietal junction (red circle in the picture). This area is important for empathy, the understanding of others’ thoughts and intentions, and verbal working memory used for expressing thought. It may function in the retrieval of sounds and patterns that give rise to musical expectations.

Synchronous brain activity was localised in the left hemisphere of the brain, to an area known as the temporal-parietal junction (red circle in the picture). This area is important for empathy, the understanding of others’ thoughts and intentions, and verbal working memory used for expressing thought. It may function in the retrieval of sounds and patterns that give rise to musical expectations.

But it is the right brain hemisphere that is most often associated with interpretation of musical melody—in contrast to the left hemisphere, which is specialised for the interpretation of speech. In the right hemisphere, synchronisation was localised to areas involved in recognising musical structure and pattern (the inferior frontal cortex) and interpersonal understanding (the inferior frontal and postcentral cortices). These sites also involve “mirror neurons,” brain cells that are thought to enables a mirroring or internalisation of others’ thoughts and actions.

Mirror neurons both control movement and respond to the sight of it, giving rise to the notion that their activity during passive observation is a silent rehearsal for when they become engaged in active movement. They were once thought to be a biological substrate for mimicry and, more importantly, empathy—the source of our understanding of the actions and intentions of others. Mirror neurons have been implicated (rightly or wrongly) in everything from autism to substance abuse. Nevertheless, nerves that control movement are generally involved in perception as well. And this arrangement is especially true of music, in which physical movement emphasises melodic gesture or follows a rhythmic beat. Indeed, the auditory cortex enlists other regions of the brain that control movement, showing an innate connection between movement and our understanding of music. No wonder you and your fellow concertgoers dance and move to the music. It is your way of comprehending the music and participating in the encounter.

Mirror neurons both control movement and respond to the sight of it, giving rise to the notion that their activity during passive observation is a silent rehearsal for when they become engaged in active movement. They were once thought to be a biological substrate for mimicry and, more importantly, empathy—the source of our understanding of the actions and intentions of others. Mirror neurons have been implicated (rightly or wrongly) in everything from autism to substance abuse. Nevertheless, nerves that control movement are generally involved in perception as well. And this arrangement is especially true of music, in which physical movement emphasises melodic gesture or follows a rhythmic beat. Indeed, the auditory cortex enlists other regions of the brain that control movement, showing an innate connection between movement and our understanding of music. No wonder you and your fellow concertgoers dance and move to the music. It is your way of comprehending the music and participating in the encounter.

Because music is a group endeavour, it is often used as the context to study coordinated brain function. Synchronised brain responses among music listeners have been measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in some studies, while other researchers have examined the coordinated actions of performers by tracking the electrical activities of their brain using electroencephalography (EEG). Rather than examine the relationship among groups of performers or groups of listeners, the new NeuroImage study examined the relationship between an audience and a performer. And it not only followed the degree of concordance in brain activity among these individuals during a musical encounter but also examined how that concordance was related to musical enjoyment. The brain activity of that person playing air guitar at your concert (oh no – someone realy was watching me!) is closer to that of a true performer than you might have realised.

Because music is a group endeavour, it is often used as the context to study coordinated brain function. Synchronised brain responses among music listeners have been measured by functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in some studies, while other researchers have examined the coordinated actions of performers by tracking the electrical activities of their brain using electroencephalography (EEG). Rather than examine the relationship among groups of performers or groups of listeners, the new NeuroImage study examined the relationship between an audience and a performer. And it not only followed the degree of concordance in brain activity among these individuals during a musical encounter but also examined how that concordance was related to musical enjoyment. The brain activity of that person playing air guitar at your concert (oh no – someone realy was watching me!) is closer to that of a true performer than you might have realised.

The various methods used in exploring these relationships have their advantages and shortcomings. For example, the new paper used a technique called functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS)—which measures the flow of oxygen-rich blood—and it cannot penetrate the brain to investigate deeper structures as well as fMRI does. The major advantage of fNIRS is that no large, expensive instrument is needed so subjects are comparatively unconstrained when they are tested: it would have been impossible for a violinist to play in an MRI machine.

It is remarkable that the observed degree of synchronisation between the performer and audience was connected to enjoyment of the music. Such pleasure could provide a powerful means by which music promotes positive social behaviour. The pleasantness of music has been attributed to synchronisation of electrical activity in the right hemisphere of the brain. Music commands greater attention when it is pleasant, which could contribute to one’s feeling of being swept away when listening to a favorite piece. While the authors of the NeuroImage paper suggest that the audience’s enjoyment was linked to the music matching pattern expectations, other studies have shown that surprise is associated with the greatest degree of musical pleasure. Remarkably, even sad music can bring great enjoyment. For example, Mimì’s illness and death in the opera La Bohème is filled with tragic sadness, endless regrets and lost opportunities for redemption, but the music ultimately leads the audience to a bittersweet sense of transcendence.

It is remarkable that the observed degree of synchronisation between the performer and audience was connected to enjoyment of the music. Such pleasure could provide a powerful means by which music promotes positive social behaviour. The pleasantness of music has been attributed to synchronisation of electrical activity in the right hemisphere of the brain. Music commands greater attention when it is pleasant, which could contribute to one’s feeling of being swept away when listening to a favorite piece. While the authors of the NeuroImage paper suggest that the audience’s enjoyment was linked to the music matching pattern expectations, other studies have shown that surprise is associated with the greatest degree of musical pleasure. Remarkably, even sad music can bring great enjoyment. For example, Mimì’s illness and death in the opera La Bohème is filled with tragic sadness, endless regrets and lost opportunities for redemption, but the music ultimately leads the audience to a bittersweet sense of transcendence.

Whether encountered as a sole listener of a recorded artist or as part of a packed audience before a full orchestra, music is a shared experience that integrates our intellect, emotions and physical movements. We tap to the beat together and sway in unison to a melody. The experience challenges our cognition to recognise patterns and excites us with pleasure when it surprises us. And we can even enjoy its expression of sadness. Music unites these processes within us and among and between audiences and performers.

Whether encountered as a sole listener of a recorded artist or as part of a packed audience before a full orchestra, music is a shared experience that integrates our intellect, emotions and physical movements. We tap to the beat together and sway in unison to a melody. The experience challenges our cognition to recognise patterns and excites us with pleasure when it surprises us. And we can even enjoy its expression of sadness. Music unites these processes within us and among and between audiences and performers.

References

The averaged inter-brain coherence between the audience and a violinist predicts the popularity of violin performance.

Hou et al. NeuroImage, Volume 211, 1 May 2020, 116655.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116655

Listening to Musical Rhythms Recruits Motor Regions of the Brain

Joyce L. Chen et al. Cerebral Cortex, Volume 18, Issue 12, December 2008, pages 2844–2854

https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhn042

Inter-subject synchronization of brain responses during natural music listening

Daniel A. Abrams et al. Eur J Neurosci. Volume 37(9), May 2013 May, pages 1458–1469.

doi: 10.1111/ejn.12173

Brains “in concert”: Frontal oscillatory alpha rhythms and empathy in professional musicians

Claudio Babiloni et al NeuroImage, Volume 60, Issue 1, March 2012, pages 105-116.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.12.008

Fronto-temporal theta phase-synchronization underlies music-evoked pleasantness

AlbertoAra and JosepMarco-Pallarés, NeuroImage, Volume 212, 15 May 2020, 116665

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116665

Lost in music: Neural signature of pleasure and its role in modulating attentional resources

Samaneh Nemati et al. Brain Research, Volume 1711, 15 May 2019, Pages 7-15

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2019.01.011

Uncertainty and Surprise Jointly Predict Musical Pleasure and Amygdala, Hippocampus, and Auditory Cortex Activity

Vincent K M Cheung et al. Curr Biol 2019 Dec 2;29(23):4084-4092

doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2019.09.067.

It’s Sad but I Like It: The Neural Dissociation Between Musical Emotions and Liking in Experts and Laypersons

Elvira Brattico et al. Front Hum Neurosci 2016 Jan 6;9:676.

doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2015.00676.

An integrative review of the enjoyment of sadness associated with music

Tuomas Eerola et al. Physics of Life Reviews, Volume 25, August 2018, Pages 100-121